From pastoral forests to industrial farms, human organisation has progressed towards a separation between city and countryside, urban and agricultural, metropolitan and rural. These oppositions are built on the assumption of humankind’s dominion over nature and a desire to rationalise and commodify life. This productivist view of nature, at the service of humankind, became further embedded with the emergence of agrochemicals, modifying practices as well as our understanding of the natural world, to the point of transforming the physiognomy of the landscape and upending our ecosystems.

In the space of a hundred years, around a billion hectares of fertile land (the equivalent of the entire surface of the United States) has disappeared from the surface of the planet. In France, the equivalent of one département (French administrative region) is lost every seven years. This terrifying fact, which has been accompanied by a worldwide drop in biodiversity, with the rapid disappearance of huge numbers of species, shows that our relationship to the earth has changed. There will be a heavy price to pay, as soil depletion affects people too, and these increasingly unequal living conditions are beginning to turn back against humans.

While this antagonism between rural and urban worlds is turning human organisation upside down, it is also modifying the landscape. Land is now organised by function: Agricultural, Urban, Natural, with each zone given over to a single type of activity. This contemporary classification leads to an antagonism which rigidifies the land use and accentuates the separation between city and countryside.

Nobody lives in the woods any longer, nobody farms in the towns. And yet, perhaps the most resilient cities will be those that are willing to reintroduce some flexibility into the organisation of space, by encouraging diversity on very localised levels. Like in an ecosystem, a single function is carried out by several entities, and each entity carries out several functions. This principle enhances an organism’s ability to adapt because, when one entity disappears, its function is taken over by others, also creating the opportunity for change: a permanent system of connections provides renewal and continuity for life.

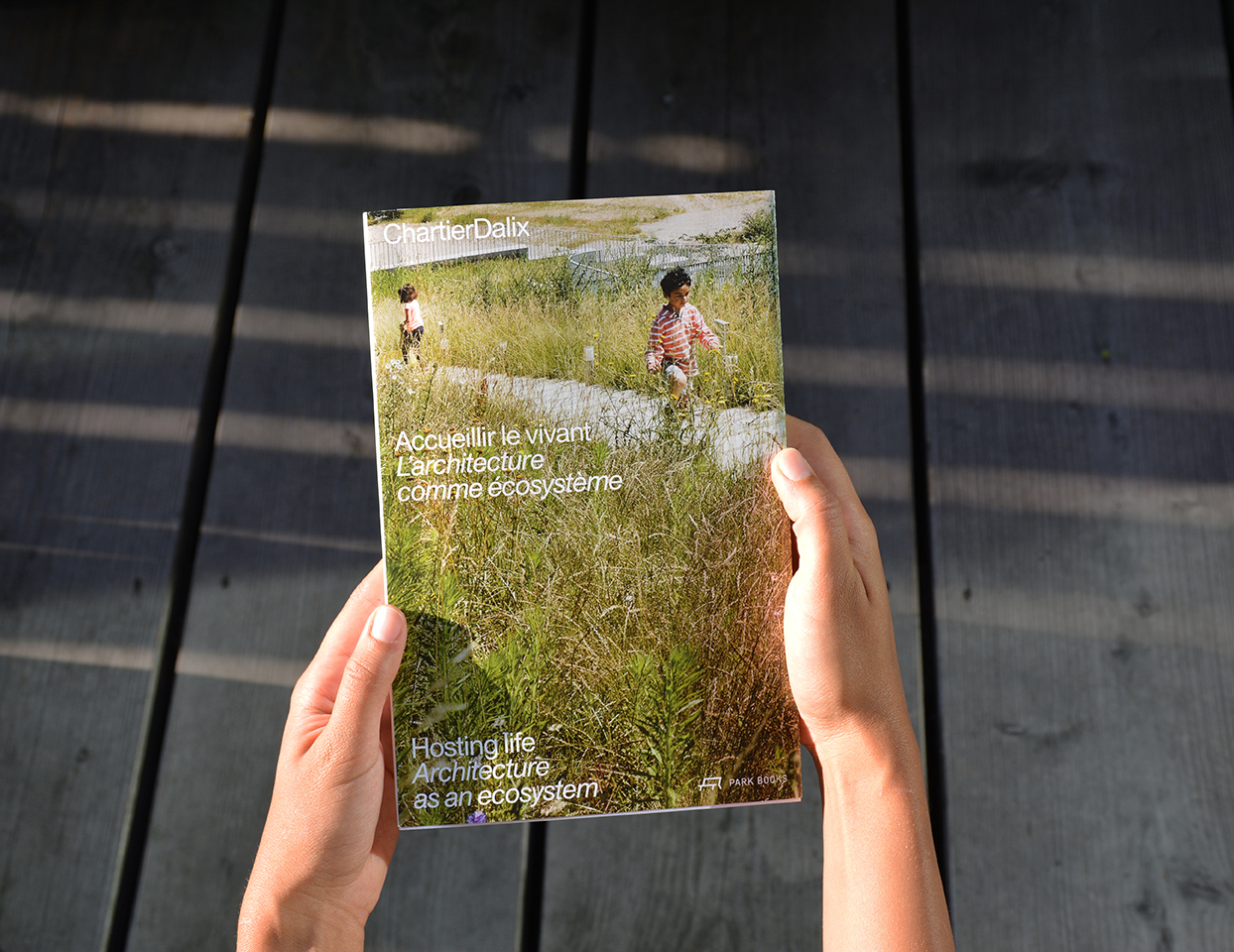

Overlapping functions, a multiplicity of uses, adding new practices to customary rules – these are some of the many intentions which can offer a new equilibrium for the cities of tomorrow. For us, this interweaving of functions is rooted in re-thinking the link between city dwellers and the living world, within the urban space itself. Integrating areas of nature means making the most of every available space to enable and encourage colonisation. It means imagining buildings which can support natural environments and guarantee that they flourish.

This practice is of particular interest to us in terms of the proximity it creates between residents and the site. Creating a laboratory of virtuous promiscuity between nature and people also allows these people to re-establish a connection with the soil, the earth, even their own built environment. Designing spaces which need to be maintained and cultivated on all scales, is a way of consolidating cohesion between humans and nature, but it doesn’t stop there. It is also a way of re-connecting with experience: doing and observing, readjusting practices along the way (rather than deciding everything from the outset). From private terraces to communal gardens, the collective experience of shared activity unites people around a common practice. The density of cities does not necessarily create social bonds, but gardens in cities1 do have this power. Greening is a way of instilling a sense of community in urban spaces, of re-thinking notions of equality and sharing. Incidentally, forums for discussion, advice and practice, as well as places to trade cuttings, seeds or more are multiplying within cities. Perhaps this is the sign of a nascent sense of eco-civic pride?

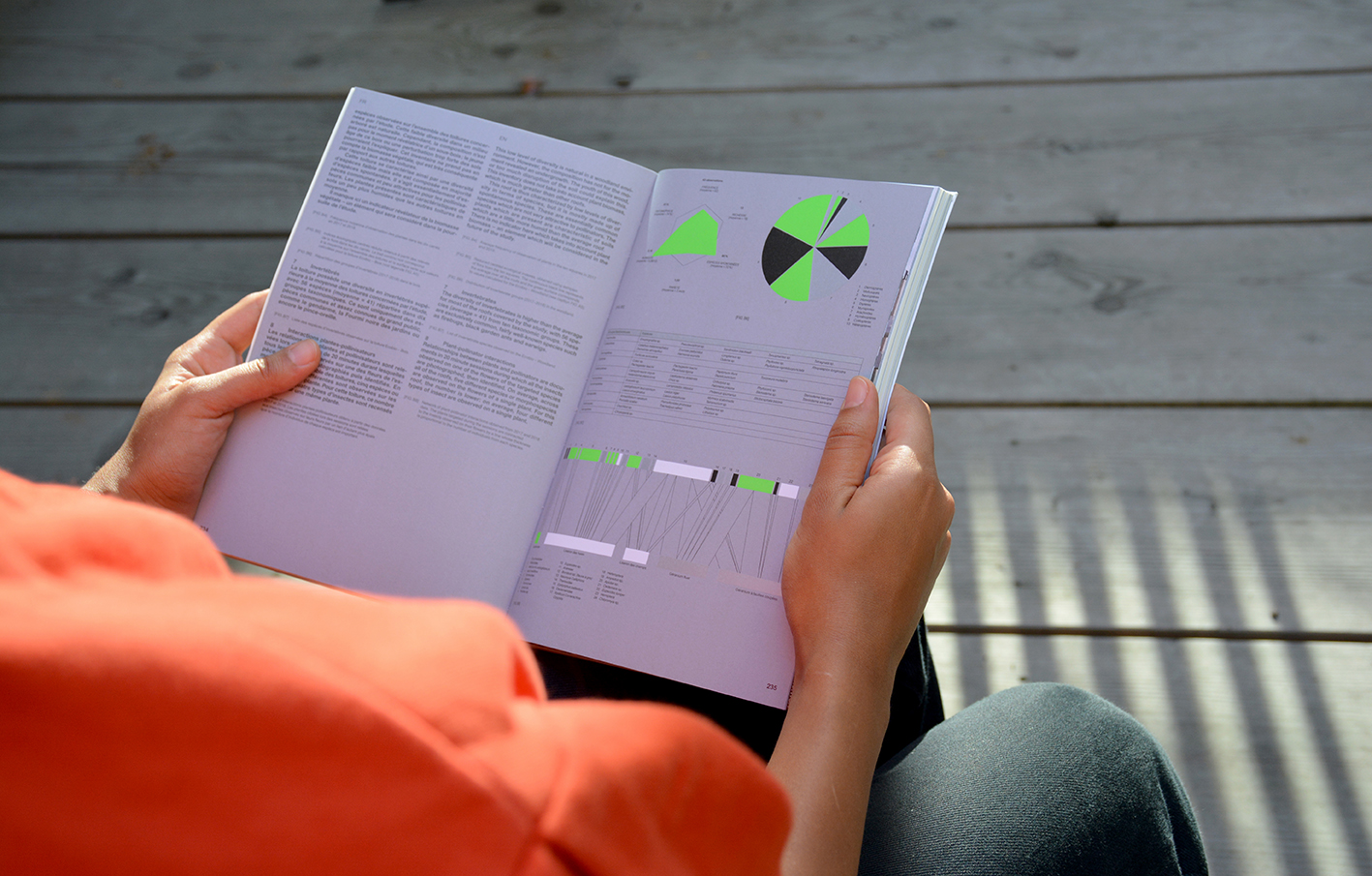

The development of agricultural spaces in cities is also playing a crucial role in the environmental transition. To a certain extent, urban agriculture can serve to provide food security and independence in the cities of tomorrow. All the more so, because it offers new modes of management, most often local, which remove the need for intermediaries between producers and consumers.

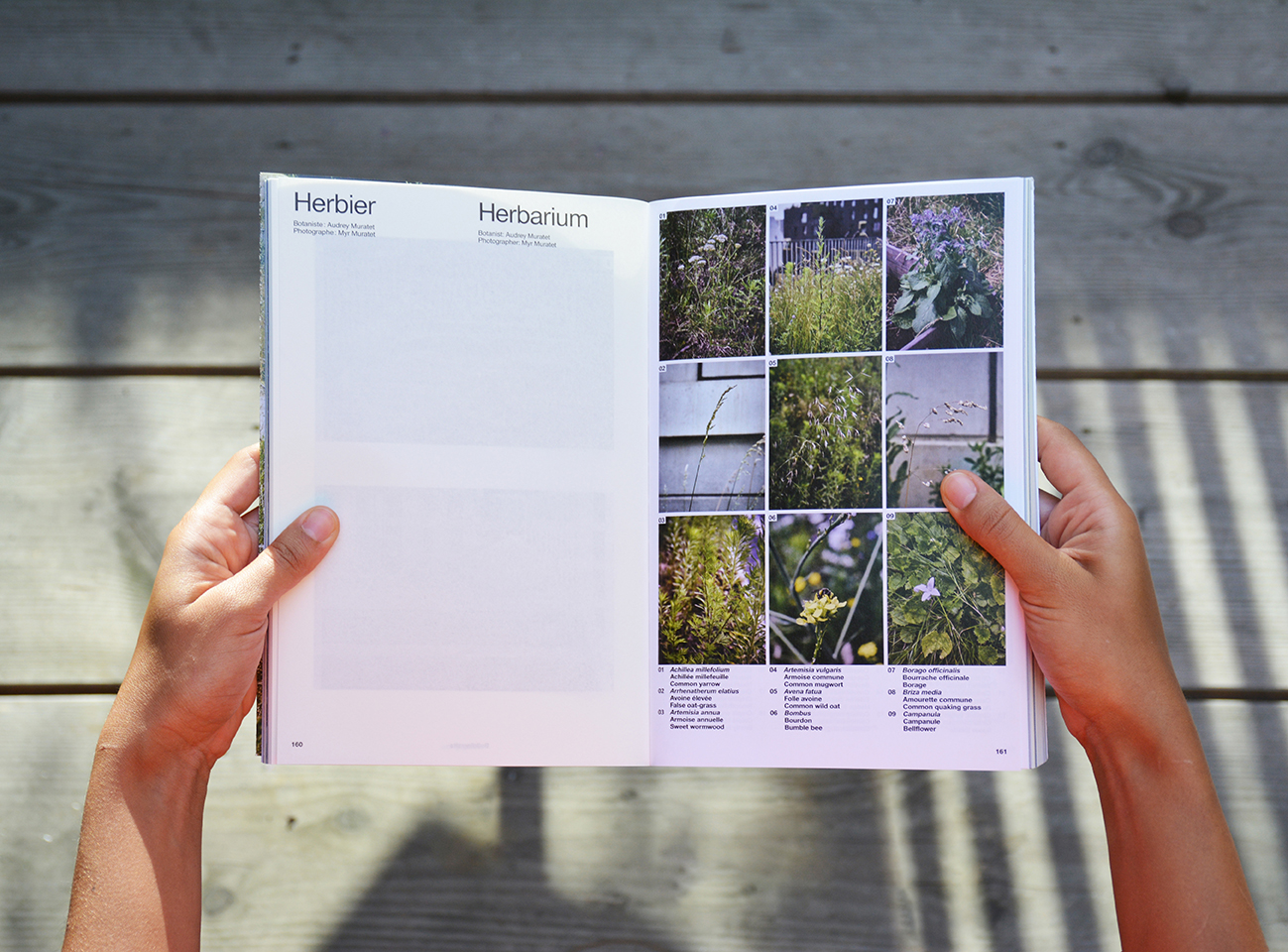

The development of these new urban functions raises the question of the physiognomy of future cities. Making space for living organisms on buildings is also, for us, a way of interrogating the fundamentals of architecture. Façades and roofs are thus re-imagined in the form of thick, nourishing envelopes. Those at the School of Biodiversity are designed to play host to fauna and flora. The topography which connects the ground, wall and roof invites a redefinition of these elements. The roof carries a forest, pedagogical gardens and animals, all of which can easily be accessed thanks to the fluidity of the grassy ramp which also forms the covered part of the playground. Each architectural element fulfils several functions, including the perimeter wall, with its inbuilt nest boxes. The same goes for the roof at Rosalind-Franklin school, which is home to a 3,500 m² prairie, and for the residential buildings at Porte des Ternes which include a tea farm as well as an entire production chain – spaces for processing, packaging, sales and tasting. The building is more than just a shelter for people, it supports nature, culture, and experiences. This idea acts as a laboratory, enabling us to test a new form of expression. We see architecture and the integration of life as different organs in the same anatomy, which complete and enhance one another in a harmonious manner.

This vision affects our conception of time, and of a “finished” building. Introducing nature as a constituent element of architecture requires accepting certain unknowns, related to how the natural environment will develop. It implies a different relationship to time and its effects, as well as a new perspective on the external appearance of our buildings.

Being colonised by the living world generates uncertainty, randomness. The ephemerality and perishability of nature requires us to revisit the concepts of completion and finitude. From this perspective, ageing becomes a key consideration: on delivery, the building is naked, empty. The more time passes, the more the vegetation develops to make up a living environment. Colonisation also implies a certain level of wear on the build surface. This runs counter to our instincts about maintenance and the positive perception of a new, freshly completed façade. Taking this variable into account means being confronted with a particular vision in which the quality of a building depends on its ageing, or even its degradation. A certain level of fragility is therefore acceptable, or even desirable, as it opens up a vast field of possibilities for integrating life.

Cracks, crevices, alcoves, cavities, overhangs, nooks and = extrusions provide spaces for species which live in close proximity to humans, making their homes in the protective and supportive habitat built by humans. Old cities already offer some of these elements in ornamental features such as cornices, capitals, and capstones. In leaving behind these ornaments, contemporary architecture provides fewer opportunities for supporting a diversity of species, which leads to a progressive sterilisation of cities. Beyond their decorative qualities, these elements, by virtue of their consistency, relief, and depth, provide a surface for connections, making them good candidates for hosting living organisms. Reinvesting in depth would offer a new field of experimentation for bringing life back into cities, giving rise to new forms of architectural expression.

This book presents several aspects of the research which we are pursuing around these topics: it starts with the two schools that we designed and built a few years ago, and now bear witness to the bonds between childhood, learning, architecture and biodiversity – these two buildings are constantly evolving and are, for us, the subject of observation and learning. The book continues with three ongoing projects which, in our eyes, illustrate the relationship between working and natural environment in the city of tomorrow. The final part presents our recent research to create multifunctional, welcoming, supportive and nourishing walls, suggesting new ways of envisioning the urban landscape.

_________________________________________________________________

1. By “garden in the city” we mean any surface which can be cultivated, vertical or horizontal, on the ground or on roofs – community and shared gardens, jointly owned property gardens, private balconies and terraces.